Live Clinically

How can physical therapists effectively develop a prognosis?

September 1, 2020

Building a plan of care (POC) and developing a prognosis are tricky endeavors. It is a combination of art and science that necessitates a clinician to consider a variety of factors that contribute to the patient’s presentation and their goals. Throughout PT School, we were provided information and advice on methods to devise a plan. It was often through a structured evaluation which sought to gather all possible information necessary to draw a conclusion on the best course of care. As my clinical career has progressed and I have read more literature, I have developed a better understanding of why that approach often falls woefully short.

What measures are the focus during an evaluation?

The idea around using a structured evaluation template to gather all necessary information certainly possesses construct validity, however, the breadth of information needed and the changing variables make collecting all relevant data in a single session nigh impossible. This is not simply an anecdotal observation and the result of a lack of skill. We are seeing this messaging spread more frequently in the evidence.

In the paper Driving the Musculoskeletal Diagnosis Train on the High-Value Track, the authors describe a clinical reasoning process to assess the complexity of low back pain and devise a course of action.[1] Typically, assessments taught in school have a heavy focus on the patient’s history and the nociceptive drivers of their pain. It is largely a pathoanatomic construct.

The subjective portion of the exam focuses on searching for a cause of the pain (e.g. an injury incident), using the patient’s description of the severity, irritability, and nature of the symptoms. The objective portion is largely focused on assessing strength, range of motion, motor control, and functional limitations (typically attributed to one of the previous three factors listed). Combine the subjective, objective, and patient goals in a pot, shake it up, and out comes the POC. Unfortunately, this misses a large portion of the necessary information.

Diversifying an evaluation

At this point, you may be nodding along while ticking off in your head all that was missed in the evaluation. Let’s go back to the paper. Decary et al. propose that the clinical reasoning process involves the following assessments: nociceptive drivers, nervous system dysfunction drivers, comorbidity drivers, cognitive-affective drivers, and contextual drivers. It is not uncommon to see the inclusion of nervous system impairments as that can include reflexes, dermatomal testing, etc. The others however are inconsistent. Clinicians obtain a list of comorbidities in the new patient paperwork, but often it strictly used to screen for red flags and as a compliance piece that needs to be added to a note.

Comorbidities extend beyond the history of cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Even as we dive into that assessment a little further, something as routine as blood pressure assessment (routine as in every single patient needs to have this assessed) can provide a wealth of information when done correctly.[2]

The authors define the comorbidity drivers as factors contributing to mental health, physical and sleep disorders. If someone is sleeping less than 6 hours a night or their sleep quality is poor, that can have a significant impact not only on the reasons the developed their symptoms, but their response to treatment and ability to recover. It is vital to address a patient’s sleep hygiene, nutritional status, dietary habits, and physical activity levels when developing a POC. In future posts, I will cover sleep, nutrition, and physical activity in more detail.

For now, I want to highlight that understanding a patient’s status doesn’t only affect how we educate and attempt to improve lifestyle habits, it affects the treatment decisions we make. Poor nutritional status and sleep hygiene impact a patient’s ability to perform a high-intensity activity and recover from treatment.

With the large push from the pain science arena of research, cognitive-affective and contextual drivers are gaining more attention, but there is still much to be desired. The frequency and thoroughness of assessing these drivers are often lagging. I have covered pain in more depth in previous posts and that is outside the intent of this one. Instead, I will highlight the cognitive-affective and contextual drivers here. Regarding the cognitive-affective drivers, these refer to the maladaptive cognitions or behaviors. Examples from Decary et al. include:

- Pain catastrophizing

- Pain-related anxiety

- Negative mood

- Fear of movement

- Pain-related fears

- Poor self-efficacy

- High illness perception

- Pain expectations

- Negative/low expectation of recovery

- Low pain coping

- Poor knowledge relating to pain science

- Facial expressions (eg, grimacing or wincing)

- Verbal/paraverbal pain expressions (eg, pain words, grunts, sighs, and moans)

- A guarded posture (eg, keeping the back straight while lifting)

- Bending/rubbing the back after performing an activity

- Completely avoiding performing a task

- Perceived injustice

- Perception that medical treatments are still needed or incomplete

- Discordance between reported behaviors (by the patient) and observed behaviors (by the therapist)

How do we assess all these drivers in the clinical setting?

Decary et al. recommends using the STarT Back Screening Tool (SBT). The psychosocial subscale (items 5-9, ranging in score from 0-5) sums factors of prolonged disability such as catastrophizing and pain-related fear and anxiety. Overall the SBT carries value as it can be used to assist with POC formation and predictability of patient response to treatment. Let’s put that aside for now and explore additional methods for assessing factors contributing to catastrophizing and pain-related fear and anxiety.

We must keep an eye out for “sustain talk”, avoidance of activity, poor coping strategies (potentially verbally lashing out, withdrawal, seeking comfort in vices, etc.), and negative facial expressions. These “findings” should be assessed and applied to our decision-making process like deficits in strength and mobility are. The cognitive-affective factors mediate objective findings in the clinic and their session to session variability.

The problem with evaluating in one session

Before reviewing the contextual drivers, it is important to expand on the previous statement regarding variability. Peter Attia is a physician but Is well known for his podcast The Drive. He earned his MD from Stanford University and a BSc in mechanical engineering and applied mathematics from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. He completed his residency in general surgery at the John Hopkins Hospital and conducted research at the National Cancer Institute. He is a fairly smart dude. Additionally, he is a former ultra-endurance athlete and he is obsessed with maximizing human performance and longevity. Despite all his experience with treating and performance, his in-depth analysis and portrayal of literature, and the wealth of knowledge he has received from his podcast guests (the interviews are in-depth, 90-120 minutes, and with top-level researchers), he still cautions against the danger of making evaluations with a single snapshot of information, regardless of the amount of information received. Here is a quote from when he was a guest on the Tim Ferris Show (transcribed from Tools of Titans)

“I’ve always been hesitant to treat a patient for any snapshot, no matter how bad it looks. For example, I saw a guy recently whose morning cortisol level was something like 5 times the normal level. So, you might think, wow, this guy’s got an adrenal tumor, right? But a little follow-up question and I realized that at 3 a.m. that morning, a few hours before this blood draw, the water heater blew up in his house. The normal level of morning cortisol assumes a guy sleeps through the night. He had to de-flood his house.”

Cortisol levels are not the only changes you would see following an early-morning for de-flooding. While this may be an extreme circumstance, it certainly isn’t the only contextual driver that may impact the patient’s presentation. It is also an acute episode, which can happen at any point in the POC and drastically alter the perceived improvement, or lack thereof. Back to the Decary article, contextual drivers are defined as the occupational and social factors that contribute to the patient’s presentation. Here are some examples:

- Low return-to-work expectations

- Low job satisfaction

- Perception of heavy work

- High job stress

- High occupational demands

- Job flexibility (nonmodifiable work or hours)

- Employer policies regarding return to work are limited or restrictive

- Poor attitudes of employer, family, or health care professionals

- Low or no access to care

- Communication barriers

Seeing all these contributing factors, you start to get an idea of how much goes into fine-tuning an ideal POC.

How do we prioritize clinical findings?

While a highly-skilled, and efficient clinician with a wealth of experience and a more refined sense of pattern recognition may be able to gather more information relevant to developing a POC in a single session, they will still fall short of all the information needed. This is not simply a lack of mental prowess and an inability to gather all relevant information, but the nature of the nonlinearity of patient presentation.

How a patient presents at 5 pm on their evaluation day may look very different than if she came in at 8 am or the following day. If we solely rely on gathering all relevant information on the first day, it is highly likely we will have an incomplete, and potentially inaccurate picture. It is crucial for clinicians to think nonlinearly. It is natural and easy to think linearly as our intuition is formed by what we observe at any given moment. It is difficult to conceptualize the ‘what ifs’ and to maintain the patience to gather information over multiple sessions. Additionally, the patient often wants answers that first day, including the projected time to recovery and completion of therapy. This brings us to the art of forecasting.

Becoming a Superforcaster®

“Without revision, there can be no improvement.”

This is a maxim from the book Superforecasting by Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner. It is a fascinating book delving into the art of forecasting, or making predictions about the future. Most forecasting studies pertain to economics, politics, and other world events, but they have remarkable applicability to patient care and devising a POC.

A key to successful prognosis and POC development is revision. If you were hoping for an innovative strategy to nail the prognosis day one with consistency, I’m sorry to disappoint. In developing a POC, allowing (forcing) yourself to revise it will improve the accuracy. Not only for the predictability of overall frequency, duration, and outcome, but for the interventions you choose in subsequent sessions.

With that said, your initial stab at the POC development and what you convey to the patient is still quite important. Your initial prescription will create an anchoring effect that can significantly impact satisfaction and adherence. For example, if you say a course of care will require 2 visits a week for 6 weeks and you later modify that to 3 times a week for 16 weeks, you will have a very unhappy patient on your hands. This leaves us with two key areas to address here: how we devise an accurate initial assessment and how we continually update our plans of care.

You must check the pride during an initial assessment. What I mean by this is seeking external information. Forecasting is far superior when aggregating external information. I am not referring to groupthink or consensus but gaining additional perspectives. This is done through a couple of means.

The importance of building Range

The first is how you gather your clinical knowledge. I’ll start with a quote from Arturo Casadevall who is a professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“I work at it, I always advise my people to read outside your field, everyday something. And most people say, ‘Well I don’t have time to read outside my field.’ I say, ‘No, you do have time, it’s far more important.’ Your world becomes a bigger world, and maybe there’s a moment in which you make connections.”

In his book Range, David Epstein explains the benefits of developing a breadth of information and skills and the dangers of over-reliance on specialization. Through reviewing mounds of evidence and cases, he has concluded that highly credentialed experts are at risk of becoming too narrow-minded. This can lead to a worsening of outcomes as experience and confidence increase.

Both Epstein and Tetlock assessed the accuracy of forecasts made by experts and they both came to similar conclusions; the results are disappointing. When experts declared that some future event was impossible or nearly impossible, it nonetheless occurred 15% of the time. When it was declared a sure thing, it failed to transpire more the 25% of the time. Taking it a step further, Tetlock was put on the map with his study that concluded the average expert was roughly as accurate as a dart-throwing chimpanzee. Here is a summary of the study provided by Tetlock in Superforcasting.

“A researcher gathered a big group of experts – academics, pundits, and the like – to make thousands of predictions about the economy, stocks, elections, wars, and other issues of the day. Time passed, and when the researcher checked the accuracy of the predictions, he found that the average expert did about as well as random guessing.”

To spice up the conclusion and add a little humor, the dart-throwing chimpanzee was added. It worked! The study was immediately gobbled up by the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, and the Economist. As you can imagine, many experts did not take kindly to this assessment and fired back. However, through mounds of data and follow-up assessments, the data is pretty clear. Expertise alone does not improve predictability over random chance. This leaves us with the following question: how do we improve our POC design so that we can improve patient adherence, satisfaction, and outcomes?

Forecasting in the clinic

Clinicians seeking to make a strong initial POC benefit from active open-mindedness. They practice extreme curiosity and are not be afraid to cross disciplines. One of the hindrances is comfort in the way evaluations are conducted. Experienced professionals tend to heavily rely on familiar tools and overlearned behaviors. Having conducted numerous evaluations with the same process makes it difficult to adopt a new one (Theory-Induced Blindness). However, if you are willing to drop a tool (no tool is “undroppable”) and evolve your evaluation process, you will become more efficient with making changes and the learning period will shorten. The other key to the initial evaluation is getting input from others.

Back to the aggregation of external information. Many of us work in a clinic with another clinician. If not, a colleague is just a phone call away. Why do I bring this up? Aggregating the judgments of people who know a variety of information is highly effective as it expands the collective pool of information. Our colleagues bring two valuable pieces to the equation: information we may not possess (both from self-study and experience) and different perspectives. They may pick up on a detail we missed or felt was unimportant. An outside view allows us to develop a more meaningful anchor to analyze. This pooling of information will allow for a more accurate forecast. However, when pooling the information and gathering an external perspective, you want to make sure it is truly an array of judgments, perspectives and opinions with evidence to back up the information.

The Benefit of Good Teams and Multiple Perspectives

There is great value in being part of a cohesive team. Trust is an invaluable component of any relationship and building it among a small group of people can yield success unmatched by individual performers. It allows for more vulnerability and openness to feedback which can in turn improve performance. This is obviously not universal and applicable to all groups. In fact, chances are you have been part of at least one group project, in either school or work, that looks like the following.

The uneven workload sews mistrust and assumptions typically go unquestioned while uncomfortable facts are left alone. Let’s say this is not a randomly assigned project with varying amounts of vested interest, but instead is a cohesive group and a well-oiled machine. This can allow you to aggregate information of varying perspectives, which is critical to high levels of accuracy when forecasting. However, the magic only happens when judgments are made independently. Enter the danger known as ‘groupthink’.

Tetlock wrote, “members of any small cohesive group tend to maintain spirit de corps by unconsciously developing a number of shared illusions and related norms that interfere with critical thinking and reality testing.” This is not to say that consensus should never happen, but you should be cautious when it does. It is imperative that we assess all angles and seek honest, objective feedback from one another.

Tetlock concludes this point writing, “A group of open-minded people who don’t care about one another will be less than the sum of its open-minded parts. A group of opinionated people who engage one another in pursuit of truth will be more than the sum of its opinionated parts…diversity trumps ability”. So how does this apply to clinicians? Consult with colleagues about your cases. Even if you are confident in your plan, seek their opinion. Again, this is not for validation and to build our confidence in our abilities, but to obtain multiple perspectives for a more accurate assessment. Then the real work begins.

The product is never finished

Once you have developed a POC, you have a starting point, not a finished product. As stated previously, patients present with a wide array of factors contributing to their presentation. Unfortunately, those factors do not remain constant, and there is nothing preventing new ones from entering the fold. The slogan for the Israeli Defense Force applies well to clinical practice. “Plans are merely a platform for change.” A plan of care is no different from any other plan.

Expert forecasters regularly seek point-counterpoint discussions, both internally and externally. They are consistently questioning whether the current plan remains accurate and the best plan of attack. This does not mean they have weak convictions. I liken it to technology forecaster and Stanford University professor Paul Saffo’s framework of “Strong Opinions, Weakly Held.” Maximize the placebo, minimize the nocebo, build patient comfort and expectations, and deliver the chosen intervention with confidence. Just be ready to abandon that intervention in the face of new information. Clinical expertise requires timely recognition of circumstances and of the moment when a new direction is needed.

William Byers, author of The Blind Spot stated, “Uncertainty is real. It’s the dream of total certainty that is an illusion.” As we reach the end of this post, you may be wondering where the technical instruction is regarding assessment and POC development. That information is out there, and it is far too robust for a blog post. Additionally, the benefit of technical information dwindles without a strong framework to apply it.

Scientific knowledge is changing every day. The frameworks for the adoption and application of new information needs to be strong in order to translate that knowledge into clinical practice effectively. My challenge to each of you (and myself) is routinely adopting the outside view. Extract the ‘wisdom from the crowd’ and boil down the information into an accurate assessment. From there, be open to frequent adjustments to the plan as you synthesize more information, both internally and externally. By taking this approach, we can provide our patients with a more accurate and personalized POC than keeps them on the path to wellness.

References

- Decary, S., et al., Driving the Musculoskeletal Diagnosis Train on the High-Value Track. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2020. 50(3): p. 118-120.

- Severin, R., et al., Blood Pressure Screening by Outpatient Physical Therapists: A Call to Action and Clinical Recommendations. Phys Ther, 2020.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

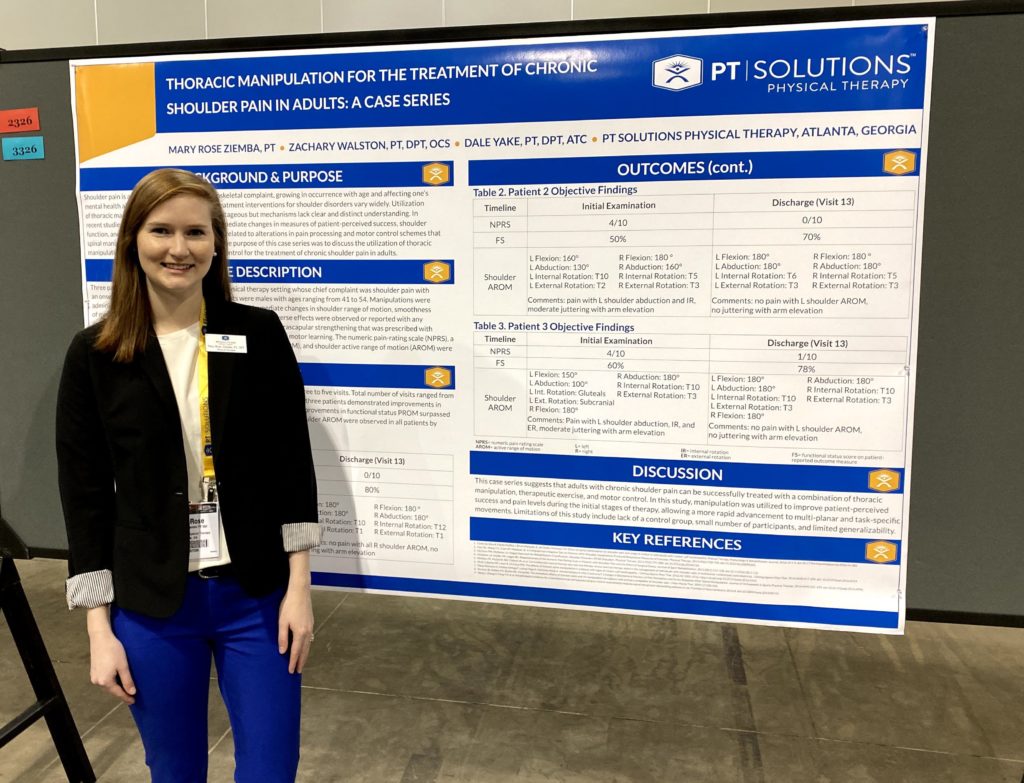

Zach has numerous research publications in peer-reviewed rehabilitation and medical journals. He has developed and taught weekend continuing education courses in the areas of plan of care development, exercise prescription, pain science, and nutrition. He has presented full education sessions at APTA NEXT conference and ACRM, PTAG, and FOTO annual conferences multiple platforms sessions and posters at CSM.

Zach is an active member of the Orthopedic and Research sections of the American Physical Therapy Association and the Physical Therapy Association of Georgia. He currently served on the APTA Science and Practice Affairs Committee and the PTAG Barney Poole Leadership Academy.