Live Clinically

Stop Focusing On The Negatives: Risks And Impairments Are Only Part Of The Patient Assessment

August 25, 2020

If you have ever tried out for a sports team or a role in a play, you have been thoroughly assessed. The coaches will notice your strengths (quick, powerful right leg, good vision of the field) and weaknesses (poor endurance, weak left leg, poor tackling). They will then use the information to make a determination of best fit on the team (better outside striker rather than a center mid) and devise training plans to either enhance strengths (maximizing peak power and sprint speed) or minimize weaknesses (improve left foot striking). This assessment of both strengths and weakness is present throughout day-to-day life in many areas. We perform comprehensive when evaluating job applicants, when dating and deciding whether to take the next step in the relationship, when choosing a career path, etc. Yet, when it comes to healthcare, the assessments tend to focus almost exclusively on the negatives.

Evaluations typically focus on “risk” factors

I’m going to paint the picture of a typical physical therapy evaluation from the patient’s point of view.

You arrive at the clinic and start the dreaded ritual of completing more paperwork than you did when buying a house. The paperwork consists of a litany of questions highlighting all the ‘problems’ with your health. Your past medical history (e.g. do you have high blood pressure, history of cancer, allergies, etc.), why you are seeking treatment, your location of pain, the severity of pain, what the pain feels like (numbness, burning, sharp, etc.), and how and when you first experienced the issue. Little do you know that this is only the beginning. Once you are called back to the treatment area, the details are layered on. Here you are asked similar questions found in the paperwork, poked, prodded, and asked to perform various types of movements that often exacerbate your pain. Following this lovely ritual, you are informed of everything wrong with you. You have weakness in your lumbar paraspinals, you have poor hip mobility, your blood pressure is high, your endurance is poor, and your nervous system is “flared up.” Translation: you are broken, and the outlook is bleak.

Now, some of you may read this, scoff, and express that you routinely focus on practice patient-centered care and a biopsychosocial approach. You routinely discredit the usage of imaging and a pathoanatomic approach to pain and dysfunction and would instead empower the patient. This is a wonderful step in the right direction. However, the focus of the session is still often on where the deficits lie, regardless of how much you focus on ‘the why’ behind them. Are you noticing how this dramatically differs from the example of sports tryouts?

In healthcare, the focus is typically very heavily geared towards risk (also referred to as vulnerability) factors while in most other professions it is focused on a combination of risk and resilience factors. By making a shift and highlighting the resilience factors of our patients, we open new possibilities when developing our plan of care and empowering our patients.

Risk vs. Resilience Factors

Risk factors are essential characteristics that are associated with an increase in health risks, such as comorbidities.1 Resilience factors are characteristics that are associated with a decrease in health risks, such as good cardiovascular fitness. Resilience has been defined as sustained positive functioning in the face of significant physical or psychological challenges.5 Sturgeon and Zautra expand the definition as “a construct reflecting overall individual well-being despite the presence of a significant stressor,” and refer to the processes of ‘resilient coping’ as “adaptive cognitive or behavioral efforts (e.g., acceptance-based coping, seeking social support) that contribute to overall resilience.”10

Patients may show a greater vulnerability (i.e. a risk) to social stressors than to physical stressors, resulting in distinct presentations in the clinic. Some patients may present with several risk and resilience factors that are related and work simultaneously, significantly impacting the patient’s response to an adverse or stressful event (such as pain provocation tests or the reading of an MRI). This is a key reason why it is critical to consider the independent contributions of both resilience factors and risk factors in defining adaptation to pain. Take another look at common assessments conducted by a clinician and which category they would fall in.

Risk:

- MRI showing disc herniation, osteophytes, and canal narrowing

- Outcome questionnaire: scores your ‘level of disability’

- Intake paperwork highlighting pain

- Asking about pain

- Pain provocation testing

- Strength testing: mentions and documents areas of weakness

- Range of motion testing mentions and documents areas of restriction

- Postural assessment: note “deficits”

Resilience:

- …

Notice any issues here? The entire visit is focused on patient “deficits” and fails to acknowledge the positives they bring to the table. What if we took a similar approach to coaching or teaching and sought the strengths in an effort to support the treatments we choose?

Finding the positives

A patient’s lifestyle factors can be a detriment and hinder the recovery process (poor diet, lack of sleep, high levels of stress) or it can enhance the interventions and allow for a more aggressive approach (healthy diet, routinely obtains adequate sleep, sufficient social support, positive affect). When performing the physical assessment, highlight the areas a patient is strong or has good mobility. Not only can this be used to enhance the intervention choices, but it can also boost the mood of the patient rather than conveying a message that their body is broken and doomed. Let us break down risk and resilience further and explore ways to implement new strategies into our treatments and evaluations.

We may be contributing to a patient’s pain experience if we only focus on the negatives

Our understanding of pain continues to evolve rapidly.11 A key area to focus on is the adaptation to pain. This complex phenomenon comprises of emotional and cognitive reactions to pain, automatic and conscious attempts at coping with pain, and social and physiological contributions to pain reactivity.9 When assessing the influence of our words and actions in the clinic, it is imperative we address pain catastrophizing.

Pain catastrophizing can be defined as “an exaggerated cognitive and affective reaction to an expected or actual pain experience,” and is characterized by “magnification of the potential negative aspects of pain, an inability to disengage from thoughts about pain, and a feeling of helplessness in coping with pain.”9 It is vital to consider pain catastrophizing as research demonstrates it contributes to greater daily levels of emotional distress, predicts greater levels of physical dysfunction and occupational interference, and is closely related to pain intensity and depression.9 Individuals who catastrophize about their pain typically implement ineffective pain coping strategies as a result of “narrowing” their focus on the potential signals and dangers of pain.3 We exacerbate this narrowing by focusing our examination and interventions on risk factors. This cognitive and attentional narrowing may reduce a patient’s ability to seek out and identify potential social and physical resources. Instead, they may create a heavy reliance on coping strategies (ones that may be obviously negative to us, and perhaps to them as well but they do not care at that moment), which leads to further pain exacerbation and potentially detrimental effects on emotional functioning. It is necessary to reorient a patient’s focus on the environment at large to foster a more flexible and resilient response to stress and pain, allowing for a reduction in the narrowing effects of pain catastrophizing.

The power of positive emotion

Among the most important psychological contributors to individual well-being and resilient stress responses are positive emotions. Positive emotions are powerful and have demonstrated significant benefits in physical well-being. Evidence has demonstrated their ability to hasten recovery from surgery, enhance immune system functioning, and increase tolerance for physically uncomfortable stimuli.9 Positive emotions may also buffer individual reactivity to pain. They reduce the frequency of pain catastrophizing and enhance individual well-being by regulating negative emotional states and strengthening social ties.4 According to the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotion, a positive affect may aid in physical and emotional well-being and recovery from negative emotion by identifying opportunities in the environment.4 Given this information, we can use positive affect to counter the cognitively narrowing effects of pain and pain catastrophizing impacting many of our patients.

Resiliency can be separated into three separate classes: sustained engagement in desirable and valued activities, recovery from stressful experiences by returning to equilibrium, and personal growth in response to a physical or psychological challenge.12 Sustainability refers to a patient’s connection to work, family, and leisure time. Do they continue to find personal and social meaning despite current circumstances? Recovery is how quickly a patient returns to the status quo following challenging and uncomfortable events. Growth is the patient’s self-reflection and recognition of their capacity and ability to learn. It pertains to new outlooks and adaptations to a stressful experience. Those who realize some level of individual growth while in pain may also demonstrate more effective recovery, or that they exhibit a more successful process of sustainability.10

Sturgeon and Zautra highlight a useful construct called the “Purpose in Life” construct. It refers to the extent to which individuals understand their purpose and direction, have goals and beliefs that give their lives meaning, and demonstrate a high level of intention toward pursuing their goals.7 Individuals that express a stronger belief that their lives have purpose have demonstrated a higher tolerance to pain8 and more rapid recovery from surgery. 6 All of this information put together highlights the powerful impact resilience factors can have on assessment and treatment.

There is a time and place for risk factors

This does not mean risk factors do not carry value. The key is the balance of risk and vulnerability throughout the session. Clearly, we cannot ignore all risk factors and we want to ensure our patients are fully informed and grasp the potential seriousness of some of the findings. However, the overall message we provide a patient can become overwhelming and the details are subsequently lost in translation. Furthermore, many of the ‘negative findings’ are not actually negative at all. Much of the literature assessing injury risk factors fail to hold water when put through the rigors of research.2

It is important we only perform the clinical tests that are necessary and to perform them in a timely manner. If there are clear pain catastrophizing red flags, it may be better served to heavily lean towards searching for resilience factors and highlighting the positives in a session rather than focusing on the negatives in an effort to demonstrate reasons they need to be in therapy. Focusing on risk factors and harnessing nocebo is never necessary to sell the value of physical therapy.

In addition to the emotion resilience factors addressed in this post, there are many physical resilience factors that can be highlighted in a session and used to develop your plan of care. These can include physical attributes such as areas they possess sufficient or exemplary strength or endurance (e.g. a cyclist with low back pain). They could be lifestyle factors such as a patient routinely eating a healthy diet (yes, these patients do exist) or sleeping an adequate amount with good quality on a nightly basis (they exist too). These areas should be both assessed and highlighted in your treatment session. Share with the patient the positives they bring to the table and how those positives better the prognosis.

Updated resilience factors list:

- Dispositional optimism

- Positive prognosis

- Social and family support

- Acceptance

- Positive lifestyle factors (e.g. diet and sleep)

- Positive objective findings on exam

To conclude, I’m going to quote a colleague and fellow residency faculty member, Lloyd Harris. I could not have put it better myself.

Healthcare is inherently negative. If a patient was able to read our documentation of their case, they’d be gobsmacked at all the “problems” we have found with them. What if we flipped the narrative a little bit during our conversations with them and focused more on the positive traits and measures that we find and lay the emotional groundwork that way.”

References

- Bartley EJ, Palit S, Fillingim RB, Robinson ME. Multisystem Resiliency as a Predictor of Physical and Psychological Functioning in Older Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1932.

- Bittencourt NFN, Meeuwisse WH, Mendonca LD, Nettel-Aguirre A, Ocarino JM, Fonseca ST. Complex systems approach for sports injuries: moving from risk factor identification to injury pattern recognition-narrative review and new concept. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:1309-1314.

- Crombez G, Eccleston C, Van Damme S, Vlaeyen JW, Karoly P. Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: the next generation. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:475-483.

- Hood A, Pulvers K, Carrillo J, Merchant G, Thomas M. Positive Traits Linked to Less Pain through Lower Pain Catastrophizing. Pers Individ Dif. 2012;52:401-405.

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71:543-562.

- McCracken LM, Eccleston C. A prospective study of acceptance of pain and patient functioning with chronic pain. Pain. 2005;118:164-169.

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57:1069–1081.

- Smith BW, Tooley EM, Montague EQ, Robinson AE, Cosper CJ, Mullins PG. The role of resilience and purpose in life in habituation to heat and cold pain. J Pain. 2009;10:493-500.

- Sturgeon JA, Zautra AJ. Psychological resilience, pain catastrophizing, and positive emotions: perspectives on comprehensive modeling of individual pain adaptation. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17:317.

- Sturgeon JA, Zautra AJ. Resilience: a new paradigm for adaptation to chronic pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:105-112.

- Thompson K, Johnson MI, Milligan J, Briggs M. Twenty-five years of pain education research-what have we learned? Findings from a comprehensive scoping review of research into pre-registration pain education for health professionals. Pain. 2018;159:2146-2158.

- Zautra AJ, Arewasikporn A, Davis MC. Resilience: promoting well-being through recovery, sustainability, and growth. Res Hum Dev. 2010;7:221-238.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

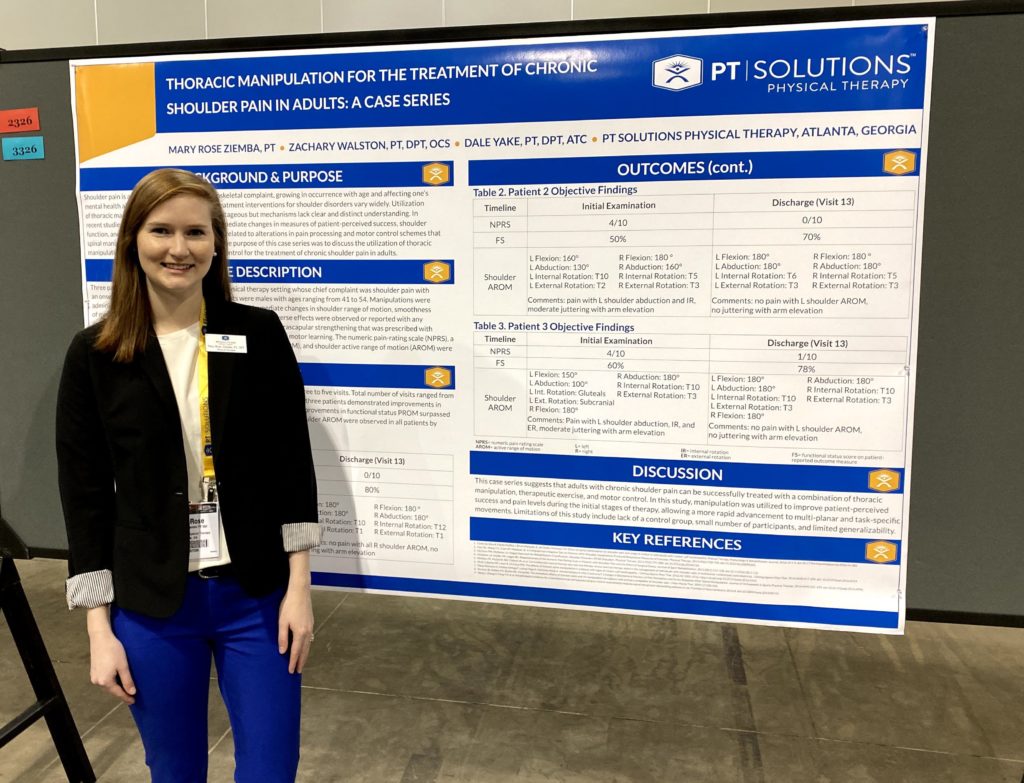

Zach has numerous research publications in peer-reviewed rehabilitation and medical journals. He has developed and taught weekend continuing education courses in the areas of plan of care development, exercise prescription, pain science, and nutrition. He has presented full education sessions at APTA NEXT conference and ACRM, PTAG, and FOTO annual conferences multiple platforms sessions and posters at CSM.

Zach is an active member of the Orthopedic and Research sections of the American Physical Therapy Association and the Physical Therapy Association of Georgia. He currently served on the APTA Science and Practice Affairs Committee and the PTAG Barney Poole Leadership Academy.