What is Pain and Why Do We Feel It?

Read Time: 5-7 minutes

“I am not what has happened to me. I am what I choose to become.” – Carl Jung

Chronic pain is more prevalent than ever, yet our understanding of it is still poor.[1] This post will focus on providing a basic understanding of pain while next week I will debunk a couple common myths. I will spare you the gritty details but if you are a nerd like me and want to dive in, I have provided references at the end for your reading pleasure.

How do we define pain?

“An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.” – International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP)

“A conscious correlate of the implicit perception that tissue is in danger” – Lorimer Moseley

The two definitions above can be simplified even more. Essentially, pain is a perception that your body is in danger of being damaged. It is an output – your brain decides if it is experiencing pain – not an input. Confused? Not a problem, as I felt the same, even after graduating physical therapy school. Let’s look at the evidence.

The original cartesian model of pain was pretty simple (see below). Tissue damage, such as burning your toe, results in pain. Essentially, the more damage that occurred, the more pain you would feel. It implies you have “pain fibers” that, when activated, signal to your brain damage has occurred and you should feel pain as a result. This model dominated our understanding of pain for centuries. While the research has progressed, many people still operate with the cartesian understanding of pain.

We don’t like change

Throughout the 20th century, particularly the second half, new theories were proposed. Unfortunately, the scientific community was slow to accept them. Enter cognitive biases. One of the primary biases delaying adoption of new theories is Theory-induced blindness. Coined by Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Laureatte and author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, theory-induced blindness refers to the phenomenon that once you use a technique with an accepted theory, it is extraordinarily difficult to notice its flaws. Theoretical beliefs are robust. Another bias at play is the confirmation bias.

This confirmation bias occurs when people seek data that are likely to be compatible with beliefs they currently hold. We tend to focus on what we know and neglect what we do not know, which makes us overly confident in our beliefs. This was perfectly illustrated by the second-century physician Galen. Setting the standard for humility, he wrote, “It is I, and I alone, who has revealed the true path of medicine.” He also provides the perfectly displays his confirmation bias when he wrote, “All who drink of this treatment recover in a short time, except those whom it does not help, who all die. It is obvious, therefore, that it fails only in incurable cases.” Some people are so convinced they have it all figured out; they ignore any new information provided. Thankfully, as more research was produced, our understanding of pain evolved and spread.

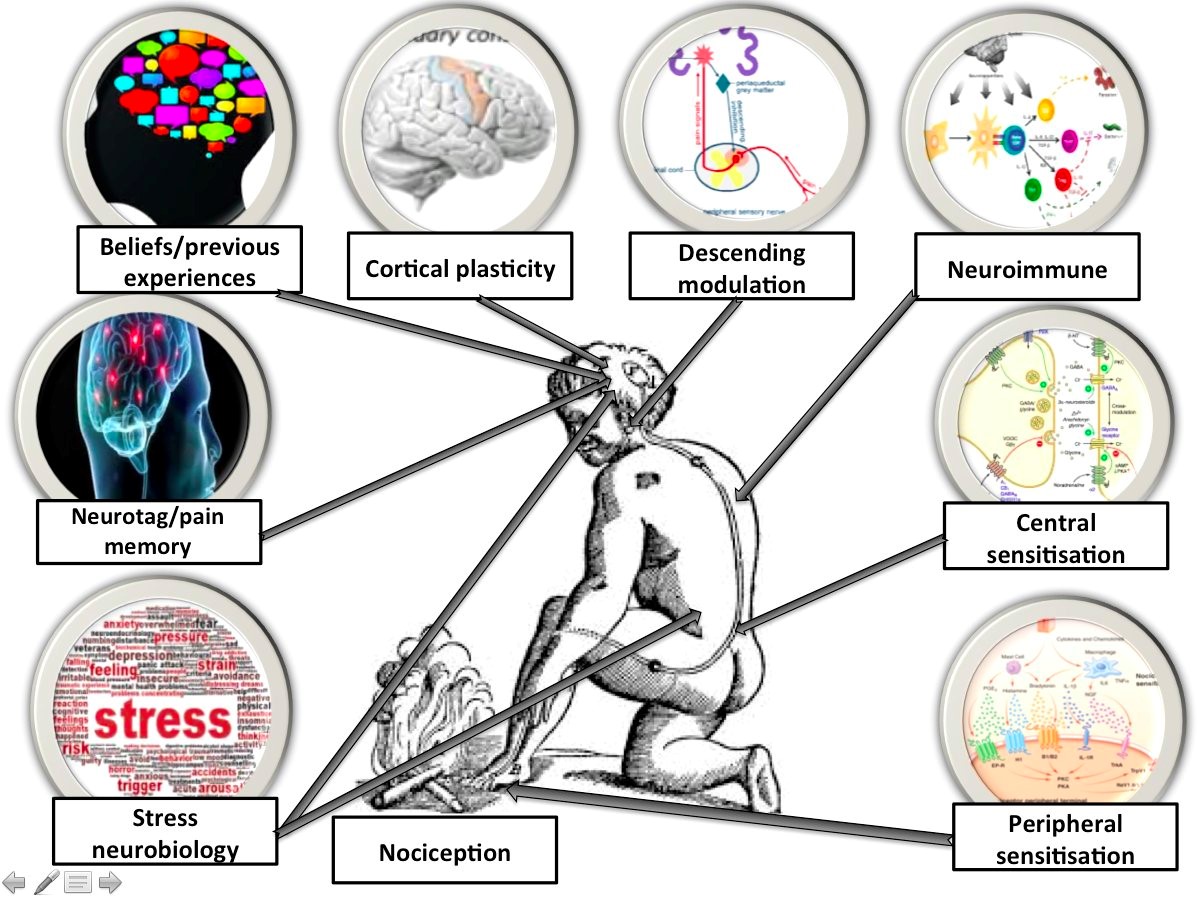

The above graphic shows how complex and how many factors influence our experience of pain. We don’t have “pain fibers” that signal specific pain. Have you ever looked down at your leg and wondered when you received that cut and why you didn’t feel any pain? Now compare that to the tiny shot or papercut you received that caused a searing, burning pain. Let’s take it one step further.

MRIs don’t tell you why you have pain

It is now well accepted that tissue damage in the spine does not equate to back pain.[2-14] A large volume of studies consistently conclude MRI results are essentially useless when determining why someone experiences back pain, except in the rare cases serious pathology, such as cancer. A majority of symptomatic patients have normal MRI reports while a significant portion of asymptomatic patients have “abnormal reports.” Furthermore, receiving an MRI is often time more harmful than beneficial.

Early MRI can lead to poorer outcomes for patients with low back pain. Early use of MRI can cause fear-avoidance behaviors, which can worsen symptoms and prolong recovery. Using advanced imaging adds anywhere from roughly $2500-6600 in additional costs to the total bill for treating back or neck pain. These costs come through unnecessary additional tests, medication prescription, injections, delayed physical therapy, and lost time at work.

Pain is complex and a single blog post barely scratches the surface of explaining it. But don’t worry, I will dazzle you with more fun facts in future posts. With that said, let’s look at some of the things we do know.

Pain involves social and psychological factors in addition to biological

Psychosocial factors, including anxiety, depression, attitudes and beliefs, social context or work status may all play an important role in the pain experience. We have nerve fibers called ‘nociceptors’ which have been misclassified as ‘pain fibers’ often. While they often do stimulate acute or immediate pain – through intense heat or cold, significant pressure or physical damage, or chemical damage – this signal can be ignored by the brain (refer to above example of cutting your leg). Essentially, our brain receives a lot of information constantly and has to apply a filter. If our attention is drawn away from the stimulus that usually causes pain, it will be diminished and potentially non-existent. Conversely, if you are hyper aware and focused on the pain then it is intensified.

Our emotional status and history of pain can significantly impact our pain experiences as well. This is a primary reason why chronic pain is so prevalent and difficult to treat. When we experience pain for a prolonged period – beyond the time needed for normal healing – our nervous system becomes hypersensitive. Other stressors such as poor quality or insufficient sleep duration, poor nutrition, inactivity, other medical conditions and, well, stress (job, kids thinking sleep is optional, being a Browns fan, etc.), can lead to a heightened pain response. This causes traditional treatment approaches (e.g. surgery and medication) to be ineffective as they fail to treat the nervous system and the multiple factors contributing to the pain (why MRIs are not very helpful).

Can we just ignore the pain? Sometimes

A good way to illustrate the power of the mind is the way kids handle pain. If you ever watch an eighteen-month old trip and fall, his first response is often to look for cues on how to respond. The child has no idea how to interpret the sudden unpleasant sensation he feels in each scraped knee and the palms of his hands. Instead, he looks to his parents for cues as to the appropriate response. If Dad runs over and asks little Johnny if he is okay, Johnny immediately is cued that something must be wrong, and subsequently revs up the crying engine. Conversely, if Dad starts clapping and saying, “great catch!” and then lures Johnny’s attention to the ball he was chasing, all is forgotten. Now, this does not mean to ignore all potential harmful events and tell your son to wipe some dirt on his broken leg after falling out of a tree. It does however illustrate the impact our mindset and experiences have on the perception of pain.

So, what does this mean for you? First, if you are in pain, there are treatment options for you, and it is more than popping a couple pills or going under the knife. Treating the whole body is necessary and very effective.[15-22] The key is finding the right healthcare professionals who can guide you on a path to recovery. Ultimately, it is your actions that will lead to recovery and wellness. Clinicians are simply here to help steer you in the right direction.

References

- Andrews, P., M. Steultjens, and J. Riskowski, Chronic widespread pain prevalence in the general population: A systematic review. Eur J Pain, 2018. 22(1): p. 5-18.

- Brinjikji, W., et al., Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2015. 36(4): p. 811-6.

- Carragee, E.J., et al., Discographic, MRI and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain. Spine J, 2005. 5(1): p. 24-35.

- Flynn, T.W., B. Smith, and R. Chou, Appropriate use of diagnostic imaging in low back pain: a reminder that unnecessary imaging may do as much harm as good. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2011. 41(11): p. 838-46.

- Fritz, J.M., G.P. Brennan, and S.J. Hunter, Physical Therapy or Advanced Imaging as First Management Strategy Following a New Consultation for Low Back Pain in Primary Care: Associations with Future Health Care Utilization and Charges. Health Serv Res, 2015. 50(6): p. 1927-40.

- Graves, J.M., et al., Health care utilization and costs associated with adherence to clinical practice guidelines for early magnetic resonance imaging among workers with acute occupational low back pain. Health Serv Res, 2014. 49(2): p. 645-65.

- Graves, J.M., et al., Factors associated with early magnetic resonance imaging utilization for acute occupational low back pain: a population-based study from Washington State workers’ compensation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2012. 37(19): p. 1708-18.

- Haig, A.J., et al., Spinal stenosis, back pain, or no symptoms at all? A masked study comparing radiologic and electrodiagnostic diagnoses to the clinical impression. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2006. 87(7): p. 897-903.

- Jarvik, J.J., et al., The Longitudinal Assessment of Imaging and Disability of the Back (LAIDBack) Study: baseline data. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2001. 26(10): p. 1158-66.

- Kalichman, L., et al., Changes in paraspinal muscles and their association with low back pain and spinal degeneration: CT study. Eur Spine J, 2010. 19(7): p. 1136-44.

- Kalichman, L., et al., Computed tomography-evaluated features of spinal degeneration: prevalence, intercorrelation, and association with self-reported low back pain. Spine J, 2010. 10(3): p. 200-8.

- Kalichman, L., et al., Facet joint osteoarthritis and low back pain in the community-based population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2008. 33(23): p. 2560-5.

- Smith-Bindman, R., et al., Trends in Use of Medical Imaging in US Health Care Systems and in Ontario, Canada, 2000-2016. JAMA, 2019. 322(9): p. 843-856.

- Webster, B.S. and M. Cifuentes, Relationship of early magnetic resonance imaging for work-related acute low back pain with disability and medical utilization outcomes. J Occup Environ Med, 2010. 52(9): p. 900-7.

- Almeida, T.F., S. Roizenblatt, and S. Tufik, Afferent pain pathways: a neuroanatomical review. Brain Res, 2004. 1000(1-2): p. 40-56.

- Apkarian, A.V., J.A. Hashmi, and M.N. Baliki, Pain and the brain: specificity and plasticity of the brain in clinical chronic pain. Pain, 2011. 152(3 Suppl): p. S49-64.

- Booth, J., et al., Exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: A biopsychosocial approach. Musculoskeletal Care, 2017. 15(4): p. 413-421.

- Gatchel, R.J., et al., The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull, 2007. 133(4): p. 581-624.

- Jafri, M.S., Mechanisms of Myofascial Pain. Int Sch Res Notices, 2014. 2014.

- Lumley, M.A., et al., Pain and emotion: a biopsychosocial review of recent research. J Clin Psychol, 2011. 67(9): p. 942-68.

- Melzack, R. and J. Katz, Pain. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci, 2013. 4(1): p. 1-15.

- Moseley, G.L., Teaching people about pain: why do we keep beating around the bush? Pain Manag, 2012. 2(1): p. 1-3.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Zach Walston (PT, DPT, OCS) grew up in Northern Virginia and earned his Bachelor of Science in Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. He then received his Doctorate of Physical Therapy from Emory University before graduating from the PT Solutions’ Orthopaedic Residency Program in 2015.

Zach has numerous research publications in peer-reviewed rehabilitation and medical journals. He has developed and taught weekend continuing education courses in the areas of plan of care development, exercise prescription, pain science, and nutrition. He has presented full education sessions at APTA NEXT conference and ACRM, PTAG, and FOTO annual conferences multiple platforms sessions and posters at CSM.

Zach is an active member of the Orthopedic and Research sections of the American Physical Therapy Association and the Physical Therapy Association of Georgia. He currently serves on the APTA Science and Practice Affairs Committee and the PTAG Barney Poole Leadership Academy.